One Sentence Abstract: Cultural and institutional factors make convergence and Euro resolution difficult, but the costs and risks of a periphery exit are also very difficult to face.

Lewis did

an excellent job describing the national character and institutions of

financial crises and nations through both anecdotal vignettes and sociological

observations. What jumped out at me throughout the book, was the enormous cultural

difference of each nation, especially Germany and Greece. If this is the case

for just two of the Eurozone countries, it seemed likely, and somewhat

disheartening, for Eurozone economic convergence. This led me to reflect on an

event over the late summer, the Greek elections and subsequent Greek exit

concerns. During this period, there was a sharp worry that Greece would exit

the Eurozone.

Default and exit was, in a very real sense, very close to

being embedded in the Greek culture as the population squirmed under heavily

persistent austerity measures and abysmal growth. The differences between

Eurozone natures had the potential to cause enormous economic turmoil. The

threat of Greek exit has subsided since its pre-election peak, the worry

persists as the crisis has been given a central bank “band-aid” but no fundamental

fix. This raises the important question, “what would a Greek Euro exit look

like?” I quickly discovered that the answer to this question is enormously

complex and uncertain, but likely results can be painted in broad strokes, into

two potential exit scenarios: managed and disorderly.

First the orderly. What one might expect under an orderly

Greek exit from the Eurozone is to start with a revocation of bailout terms.

What this means is that the Greek government refuses to enact the required

austerity reforms imposed by the IMF and required from ESM/EFSF. However, under

a managed scenario, the parting of the Greeks from the Euro is at least

partially mutual. This is important for a number of reasons, and allows the

Euro government to help both limit damage in Greece, but also limit the

contagion impact of a country leaving the Euro. This type of exit would likely

be accompanied by support for financial institutions with exposure to Greece

(may of the European FI’s have already limited their direct exposure to a Greek

exit, but remain exposed in terms of secondary effects). We might expect to see

a firewall for the remaining IIPS, with the ECB and other international

monetary funds acting to ensure financial stability by injecting liquidity. A

managed exit would require a plan to be put together in secret, and implemented

along with severe capital restrictions. To illustrate why, imagine you are a

Greek citizen who becomes aware that all of your assets will be redenominated

in new-Drachma next week. This new currency will immediately inflate and become

worth less and thus your net wealth will take a large hit.

Would it make any sense to hold your assets in Greece and

allow this to happen? No. This illustrates the danger of capital flight should

this plan become known before capital movement restrictions are put into place.

Should this downside realize, we would see something more akin to the

disorderly resolution mentioned below.

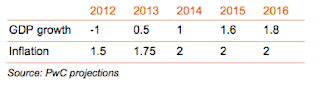

Applying some numbers to this scenario, we see something

along the lines of the following PwC projections for Greece (assuming fiscal

reform post exit, a very optimistic

assumption, I believe its more likely for less growth in the 5 year period,

especially given the subsequent Eurozone slowdown after this report was

published):

Similarly for the Eurozone:

A Greek exit has negative growth impact, especially in the

short term, and especially for Greece. It would also likely lose access to

capital markets and thus still be dependent on the IMF.

The Greek economy does not make up a large percentage of the

Eurozone, in fact it is only about 2% of the total:

Given the small size of the Greek economy, a large portion

of the worry of a Greek exit its impact given the interconnection between

Greece and the rest of the periphery as well as connections to the Eurozone

core. Without the policies aimed at dampening the contagion impact of a country

exiting the Eurozone, a Greek exit would be much more damaging. We would expect

a large, negative world impact from a disorderly exit. A disorderly exit

increases the risk of other periphery nations exiting. At the very least, the

borrowing costs for these nations would dramatically increase alongside weak

growth. Even without going very far into the weeds of how these policies would

be enacted, it becomes apparent how difficult and fraught with downside risk a

Grexit would be.

After reading Boomerang

and exploring what a broken-up Eurozone would look like I am left with two

important impressions. First, the culture of the more productive, creditor

Eurozone nations is significantly different from the debtor, Sunbelt nations

(as represented by Greece). It seems unlikely, given the history and long-term

trends of the cultures and institutions in both areas that the sort of economic

and institutional convergence that would be required to fix the Euro will

occur. Similarly, the political problems creating a fiscal union to match the

existing monetary union are very difficult to overcome. However, the

alternative in which the Euro is dissolved is extremely untenable. Like it or

not the Euro has significantly tied these countries together, and breaking it

up would be extremely painful, not only for the countries directly involved in

the break-up, but also profound world-wide recession. Understanding the

divergence in institutional and cultural characteristics of these nations along

with the costs of splitting-up, illustrates just how difficult this situation is

to resolve.

No comments:

Post a Comment